About Us

Expertise

PRACTICE AREAS

Publication

Careers

APplication Process

Join Our Team

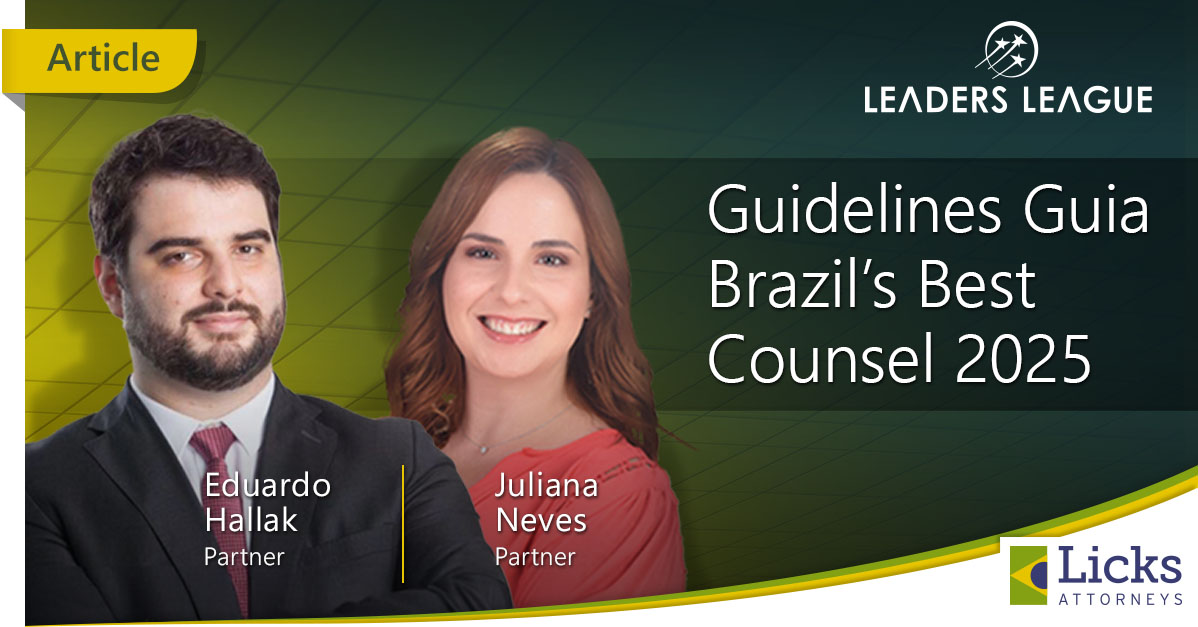

Eduardo Hallak is one of the founding partners of Licks Attorneys and heads the firm's São Paulo office. For over 20 years, he has been working in several complex disputes and leading cases involving Patent and Regulatory Compliance, most of them pursuing the interests of clients in the field of Life Sciences. Mr. Hallak teaches IP litigation in a Postgraduate course at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUCRJ), also taking part in INTA’s Enforcement Committee.

Juliana Neves is a partner at Licks Attorneys, seated at the São Paulo office. With over a decade of experience, Ms. Neves is an expert in Intellectual Property and Administrative Law, dealing with highly complex IP and regulatory litigation, mostly defending the interests of clients in the field of Life Sciences. Ms. Neves holds a Master of Laws degree (LL.M) with the University of Chicago Law School and postgraduate degrees in Intellectual Property law from PUC-Rio and public bids and public agreements from FGV-RJ.

The Life Sciences sector is a dynamic and ever-evolving field, continuously shaped by advancements in technology and shifts in regulatory frameworks. In 2024, several pivotal events have set the stage for significant developments, influencing public policies and driving innovation. These milestones will undoubtedly impact the future direction of the Life Sciences landscape, heralding exciting prospects for the sector.

One example is the Productive Development Partnerships (PDPs) program, that has always been in the Federal Government’s agenda and just recently returned to the heat. In the recent years, and due to recommendations from the Federal Court of Auditors (TCU), the Ministry of Health (MoH) started a process of reviewing the rules applicable to PDPs. Among others, the main fragilities which urged to be tackled with concerned the lack of objective criteria for analysing PDP proposals and to define which drugs are eligible for PDPs, as well as the legal uncertainty regarding the selection of the private partner. On June 21, 2024, after a round of debates, which resulted in 1,265 different contributions from stakeholders, the MoH published Ordinance #4,472/2024 aiming to cope with such fragilities and give a new regulation to the PDP program.

With the wave of the new regulation, between June and September 2024, several Government-Owned Pharmaceutical Industries (GOPI), such as Fiocruz, Bahiafarma, and Butantan Institute, conducted public calls to select private partners aiming at submitting PDP proposals jointly to the MoH. By September 30th, the MoH received 147 PDP proposals and 175 proposals for PDILs (Local Development and Innovation Program).

Even though the MoH has not yet made available the list of PDP proposal submitted on September 30th, informing which GOPI and private partners submitted proposals and for which eligible products, according to the former Secretary of MoH’s Industrial and Health Economic Complex Department, Mr. Carlos Gadelha, the proposals were mainly for projects in the fields of Digital Health (85 projects), Cancer (48 projects) and Neglected Diseases (39 projects), as well as 3 proposals for dengue vaccine, 6 local innovation proposals focused on diagnostics and 1 proposal for the treatment of said disease.

In December 2024, the MoH published Rule #1/2024, setting up the new Internal Regulations of the Technical Assessment Commission (CTA), addressing, among others, the roles and operational procedures of CTA within the PDP framework and the creation of a scoring system for PDP proposals to serve as the criteria for analyzing and classifying them.

Despite the six months that have passed since the September 30th deadline for submission of PDP proposals, so far, only two were recently approved –concerning the technologies of production of insulin glargine and the respiratory syncytial virus vaccine.

Also in 2024, the Brazilian Supreme Court ruled on new guidelines for judicialization of the supply of pharmaceutical products by the Federal Government, especially those considered high-cost products. Stemming from the trial of appeals discussing the supply of drugs to individual patients, the Brazilian Supreme Court edited topics #6 and #1,234, establishing that the Federal Government is not obliged to provide high-cost drugs judicially demanded when such products are not included in the list of drugs available in Brazil’s Unified Health System (SUS) Exceptional Drug Dispensation Program nor registered with the Brazilian Food and Drug Administration (ANVISA). The Brazilian Supreme Court also determined in cases where (i) there is an operational obstacle in procurement of pharmaceutical products, or (ii) there is a price dispute regarding the drug, it will be up to the assigned Judge to determine either (a) a discounted price proposed during the incorporation process at the MoH, or (b) the price it already costs to the Government, whichever is lower. Failure to supply the drug at the established price will result in fines.

When it comes to patent litigation in the Life Sciences sector, the Brazilian Courts have been playing an essential role in defining the landscape to the practice. For instance, a recent decision from the 1st Chamber of Business Law and Conflicts related to Arbitration of the São Paulo State Court of Appeals voided a trial court decision on the merits rejecting infringement claims from the patentee on the grounds of invalidity of the patent being asserted (i.e., metabolite patent) to acknowledge that determining whether or not there would be infringement required technical examination to be conducted by an expert in biochemistry or organic chemistry. This decision is paramount as it ensures full evidentiary production in patent infringement cases, even if it is to be determined by the Appellate Court after being dismissed by the trial court.

Moreover, the implications of the trial of Constitutional Challenge #5,529 (ADI #5,529) by the Brazilian Supreme Court are still on the go. In May 2021, the sole paragraph of Article 40 of the Brazilian Patent Statute (BPS) was declared unconstitutional voiding the provision that guaranteed a minimum of 10-years protection to patents granted after more than 10 years of examination at the Brazilian Patent and Trademark Office (BRPTO). From May 12th, 2021 onwards, all patents granted are valid for 20 years from the filing and patents that were granted under the sole paragraph of Article 40 of the BPS structure, if related to pharmaceutical treatments and products or object of invalidity lawsuits filed up to 7th April 2021 (provided that the sole paragraph of Article 40 of the BPS was cause of action) immediately had the protection term reduced to 20 years from filing.

As a result, 66 lawsuits were filed at the Federal Courts – mostly in Brasilia and one of them in Rio de Janeiro – requesting the adjustment of the protection term in view of BRPTO’s delay in examining the applications. The first wave of cases were based solely on the foreign mechanism of patent term adjustments (PTA-like lawsuits), but a second wave grounded its claims in the Brazilian legislation provisions setting forth the administrative due process and reasonable duration of administrative proceedings, as well as the obligation of the Government of compensation for damages caused by its own acts – in this case, BRPTO’s unreasonable delay in analyzing patent applications, some of which taking more than 15 years to be concluded. So far, 25 cases have been decided on the merits at Trial level, all of them being rejected. There are 15 pending appeals at the Federal Court of Appeals for the1st Circuit (TRF1), and 3 appeals have already been tried, in which the Panel upheld the decisions on the merits unfavorable to the patentees.

It is noteworthy that the Courts are not the only ones that have been facing discussions over the patent protection term. There are several pending bills of law at the Brazilian Congress discussing patent term adjustment mechanisms, the most relevant one being Bill #2,056/22 proposed to amend both the Law #5,648/1970, which created the BRPTO, and the BPS: (i) allow divisional applications after the decision that granted the patent application and, in case of rejection, until the final decision (including the appeal phase); (ii) allow claim modifications until the end of the examination phase; (iii) declare that the end of the examination phase includes the appeal phase; (iv) establish a PTA mechanism for BRPTO delays. Much more is certainly to come — and we will have to watch and see.

Previous Post

There is no previous post

Back to all postsNext Post

There is no next post

Back to all postsRegister your email and receive our updates